The Race That Shows the Bones: Part Two - What It Actually Takes to Compete

The math, the margins, and the capacity Tennessee Democrats can’t keep pretending they have.

This is part two of a four-post series on the TN-07 special election and what it reveals about the structure, strategy, and soul of Democratic infrastructure in Tennessee.

In Part One, we talked about the moment the headlines broke and why this race isn’t a breakthrough… it’s a diagnosis (read that here). Now we’re breaking down what it actually takes to win, and whether we’re even close.

It’s easy to get swept up in a headline. But campaigns aren’t built on headlines.

They’re built on numbers, logistics, and infrastructure. And those things don’t appear overnight. They’re built well before a race begins.

So let’s talk mechanics.

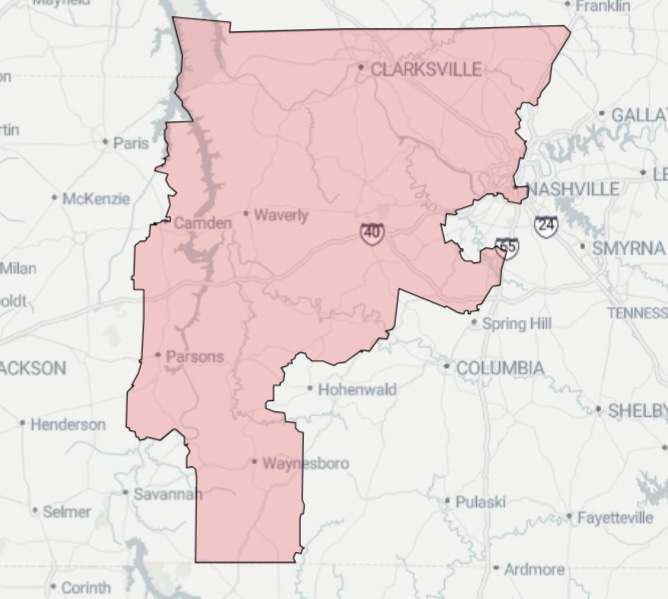

Say Tennessee’s 7th Congressional District has about 530,000 registered voters.

That number is approximate. I’ll admit, I didn’t break down every precinct line or cross-reference the shapefile to perfection. But nearly every county in the district lies fully within TN-07, except for Benton, Williamson, and Davidson, which are only partially included. I’ve already done the math for the rest, and here’s a chart so you can trust me. It’s close enough for the point I’m making.

In the 2024 presidential election, voter turnout across these counties averaged around 65%. During the 2022 midterms, turnout dropped to about 39%, which is typical. And in recent Tennessee special elections (not TN-07), turnout drops even further… hovering between 15% and 23%, depending on the district and race.

So when we look at TN-07’s upcoming special election, we’re not talking about presidential or midterm-level participation. We’re looking at something much lower - realistically in the 15–25% range, and even 30% would be optimistic unless something major changes the environment.

Here’s what that looks like when you apply it to the estimated 530,000 registered voters:

15% turnout → ~79,500 voters

25% turnout → ~132,500 voters

30% turnout → ~159,000 voters

This is where the concept of a “win number” comes in. (A win number is simply the number of votes a candidate needs to win outright.)

Basic Win Number Formula:

Registered Voters × Turnout Rate ÷ 2 + 1 = Win Number

Which means:

15% turnout → ~39,751 votes to win

25% turnout → ~66,251 votes to win

30% turnout → ~79,501 votes to win

Technically, those numbers make the race possible to win. (The “D” on the ballot in the 2024 general recieved 122,764 votes.)

But technically possible and realistically plausible are not the same thing.

Because now you have to ask:

Can we identify, reach, and turn out 40,000+ Democratic-leaning voters - in the right counties, in a compressed timeline, and without a top-of-ticket race driving turnout?

And if we’re being honest, the answer is… maybe.

That’s not a critique of any candidate. It’s not about how sharp the messaging is, how angry voters are at Trump, or how much we want this to be our Georgia moment.

This is about infrastructure, and the condition of the structure we’ve built.

Or more accurately, the structure we’ve failed to build.

Whatever happens in TN-07 (win, lose, or outperform) will not be the result of what is done do the next 100 days.

It will be the result of choices made long before June 9.

These choices include:

Which counties got resources

Which organizers were hired… or weren’t

Which candidates were supported… or ignored

Which voters were contacted consistently… and which ones were never contacted at all

This is the result of years of underwatering our own ecosystem, and then acting surprised when nothing blooms.

Because reaching a win number doesn’t just require math.

It requires capacity.

You need local parties that aren’t just technically “organized,” but actually functioning. And that means doing voter contact, developing candidates, and maintaining presence in their communities.

You need voter data that’s clean and current. You don’t need a VAN export from 2020 that nobody’s touched since.

You need a field plan that starts with turf cutting and ends with doors knocked, and for that, you need people in place. Not next month. Now.

You can’t build that in 100 days.

Especially not across fourteen counties with wildly different needs, geographies, and histories.

And if it isn’t obvious where I stand by this point:

This isn’t the fault of the volunteers.

It isn’t the fault of the candidates who stepped up, or the people giving their nights and weekends trying to hold things together.

This is a failure of a political culture; a culture that refuses to invest in long-term infrastructure because it doesn’t produce fast enough results for a press release or donor email.

We get caught flat-footed because we act like moments like this are rare accidents.

But they’re not. They’re predictable.

And serious organizations prepare for predictable things.

The best message in the world can’t patch a crumbling foundation.

A candidate can only do so much.

And even the best campaign plan in the world can’t move if the basics aren’t already there:

Who are the canvassers?

Who’s coordinating logistics in each county?

Who’s trusted in these communities?

Do we even have a walkable list in Dickson, or Perry, or Houston?

If those answers don’t exist yet, then we’re not in a position to compete.

We’re in a position to scramble.

This doesn’t mean the race is lost.

But it does mean that whatever happens, it won’t be a referendum on our ideas or our values.

It will be a verdict on our structure, and on whether the state party ever took that structure seriously.

In Part 3, we’ll zoom out and talk about the pattern behind all of this. How Tennessee Democrats keep getting caught unready, and what it’s consistently costing us.